How to Address Climate Change

This overview of Climate Change Solutions covers a wide range of solutions and systemic changes that can effectively address the climate crisis.

Climate Change Solutions

Human-related causes of climate change are eroding Earth’s ability to sustain life, resulting in a climate crisis.

Given the urgency and magnitude of this existential threat, it’s never been clearer that dramatic changes at all levels of society are needed. Whether humanity takes bold action to implement these changes will be the difference between continuing on a destructive path and ensuring a livable, thriving planet for all.

Luckily, creative and committed people around the world have identified a wide array of climate change solutions that can heal our planet as well as the injustices that frontline communities face.

Some of these solutions are technological and focus on the ecological matters related to climate change. Other solutions seek to transform the systems that underpin the climate crisis. These solutions strike at the root causes of the climate crisis, simultaneously addressing the ecological as well as the social, political, and economic aspects of climate change.

Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human-related greenhouse gas emissions—which contribute to global warming and other ecological degradation—are currently the highest they’ve ever been.

In order to address the sources of emissions, a scientific organization called Project Drawdown has identified and measured the most effective climate solutions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions today.

These solutions either reduce emissions or support nature’s carbon sinks.

How to reduce emissions

Project Drawdown's solutions fall into 9 sectors that represent 9 different areas of society:

- Food, Agriculture, & Land-Use

- Electricity

- Buildings

- Coastal Sinks

- Health & Education

- Industry

- Transportation

- Land Sinks (sequester carbon in soil)

- Engineered Sinks (sequester carbon through human engineering)

Within each sector, there are related actions that can help reduce the level of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere.

FOOD, AGRICULTURE, AND LAND USE

Actions:

- Shift diets and reduce food waste

- Protect ecosystems and avoid clearing or deforesting land

- Implement regenerative agriculture

- Plant rich diets

- Indigenous people's land management

ELECTRICITY

Actions:

- Decrease the demand for electrical production

- Replace fossil fuels with renewable energy

- Upgrade broader electricity systems with flexible grids and effective energy storage

Examples:

- Wind turbines

- Microgrids

BUILDINGS

Actions:

- Enhance energy efficiency of buildings and homes

- Shift energy sources to clean energy/renewables

- Better manage refrigerant leaks and disposal

Examples:

- Dynamic glass

- Green roofs

COASTAL SINKS

Actions:

- Protect and restore coastal ecosystems

- Shift to regenerative agriculture along coasts

Examples:

- Wetland restoration

- Wetland protection

HEALTH & EDUCATION

Actions:

- Secure gender equality

- Guarantee human rights

Examples:

- Expand access to education and family-planning, particularly for women and girls

INDUSTRY

Actions:

- Replace plastics, metals, cement, and harmful refrigerants

- Move towards a circular economy and use waste as a resource

- Shift to low-carbon sources of energy and non-carbon energy

Examples:

- Bioplastics

- Composting

TRANSPORTATION

Actions:

- Replace fossil fueled transportation

- Improve energy efficiency of vehicles

- Electrify vehicle

Examples:

- Walkable cities

- Electric trains

LAND SINKS

Actions:

- Shift diets and address food waste

- Protect and restore ecosystems

- Shift to regenerative agriculture

- Use degraded land

Examples:

- Tropical forest restoration

- Silvopasture

ENGINEERED SINKS

Actions:

- Remove, then store, bury, or use carbon

Examples:

- Biochar

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

For thousands of years, many Indigenous communities have lived in balance with nature, even enhancing the health of their local ecosystems.

This is largely because many Indigenous communities' ways of life are built upon reciprocal relationships between people and the environment. Indigneous principles like Sumak kawsay and Buen Vivir promote community well-being through coexistence with and deep care for nature. The mutually beneficial relationship between many Indigneous communities and the environment is also tied to the wealth of ecological expertise that these communities have developed over time.

This expertise, or traditional ecological knowledge, has allowed many Indigenous communities to live in such a way that allows nature to regenerate and thrive, and has also given them the ability to respond effectively to climate change.

What is traditional ecological knowledge?

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is a system of ecological scientific knowledge and practices developed by Indigenous peoples over thousands of years.

TEK includes place-specific land and resource management based on each community’s collective knowledge about their local environment. This collective knowledge is acquired through direct experience in nature and the community’s long-term relationship with the local ecosystem. It encompasses practical scientific knowledge and proven techniques, as well as cultural traditions. Unlike conventional science, TEK relates to humans as a part of nature and emphasizes the relationships within an ecosystem.

There is no single body of TEK because the ways different Indigenous communities interact with the environment vary greatly according to local conditions.

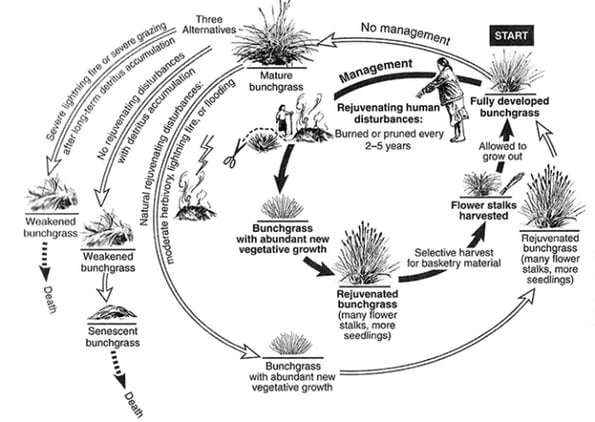

Traditional management of deergrass produces healthier plants. Image courtesy of KCET.

Traditional management of deergrass produces healthier plants. Image courtesy of KCET.

It’s important to note that TEK is not just a body of scientific knowledge and ecological techniques. It's also considered a way of life for many Indigenous communities, one in which people have a deep relationship to place and through this relationship, contribute to the balance within ecosystems.

Traditional ecological knowledge and climate change

Throughout history, many Indigenous peoples have been able to respond effectively to climate change by relying on their communities’ TEK.

TEK includes a community’s detailed, long-term knowledge of their local ecosystems. This knowledge, which can span hundreds or thousands of years, includes observations of the changes—such as shifts in weather patterns or animal behavior—that the environment has undergone over long periods of time. Being able to compare present day conditions to this historical data is key to understanding climate change impacts as well as how to adapt to or manage them.

TEK and climate resilience

Living in balance with nature is another key component of TEK that allows for both natural and human systems to be resilient in the face of environmental disruption.

For many Indigenous communities, it’s critical to live sustainably and take only as much as they need so that the ecosystem can regenerate and continue to provide for the entire community—which includes both humans and other species. Throughout history, the Indigenous communities in California harvested plants and animals at carefully considered frequencies and intensities. This allowed them to meet their communities’ needs while conserving the plant and animal populations that they took from. At times, their management of the land even increased the plant and animal populations. Cultivating a reciprocal relationship with nature allows nature to regenerate so that it can continue to support life.

Biodiversity

Living in balance with nature also protects and promotes biodiversity, which allows humans to be flexible and adaptable in the face of climate change.

Biodiverse ecosystems provide a wide range of foods, medicines, and materials that humans and other species can depend on without depleting any one source. When changes or disruptions within the ecosystem occur, such as decreased rainfall, biodiversity ensures that alternatives for sustenance are available. 80% of the world’s biodiversity is protected by Indigenous people, which goes to show the critical role that Indigenous land management plays in supporting healthy ecosystems and enhancing nature’s ability to be resilient against disruption.

Indigenous-led climate action

Given the intimate connection between many Indigenous peoples’ way of life and the land they live on, they are often more vulnerable to abrupt changes in the environment. Indigenous peoples are among the first to experience the most severe and immediate effects of the climate crisis. However, they tend to contribute the least to climate change. Land managed by Indigenous people are some of the healthiest ecosystems on the planet, and yet it’s targeted for extraction and industrial processes because of the marginalization and oppression of Indigenous communities.

Though Indigenous communities whose way of life is tied to the land are more vulnerable to the climate crisis, their connection to the land positions them to know best when it comes to responding to changes in the environment. It’s no surprise that Indigenous people have been taking the lead on climate change action for many years.

Following the leadership of those who hold their communities’ TEK provides non-Indigenous people an invaluable opportunity to learn from them. It also creates opportunities for non-Indigenous people to collaborate with and support Indigenous communities who are protecting the environment and implementing climate change solutions. It can also shed light on the unique impacts of climate change on Indigenous people whose way of life is tied to the land.

At the same time, advocating for Indigenous rights ensures that Indigenous communities are unimpeded in their ability to respond to climate change on their terms.

Indigenous rights

Though TEK is key to the health of the planet and the wellbeing of the communities for whom TEK is a way of life, significant barriers to Indigenous rights threaten the preservation and implementation of Indigenous knowledge systems and practices.

The government’s suppression of cultural burning within Native Communities in California is a clear example of the ways in which the ongoing oppression of Indigenous communities and their traditional knowledge have devastating consequences for both people and the planet.

For centuries, many Native communities in California regularly used fire on the land to encourage new plant growth, increase crop diversity and productivity, as well as clear forests of underbrush that could fuel wildfires. When settlers forced Native communities off their ancestral lands, they also banned many Native traditions, including applications of Native traditional knowledge. As a result, Native communities in California weren’t able to practice cultural burning and California has been devastated by uncontrollable wildfires that have worsened as climate change and global warming intensify.

Red skies in San Francisco after the 2020 wildfires. Image courtesy of Patrick Perkins.

Red skies in San Francisco after the 2020 wildfires. Image courtesy of Patrick Perkins.

What the settlers—and many people today—didn’t understand was that the thriving landscape they had thought was “wilderness” untouched by humans was actually in good health because of the Native peoples’ active management of the land over hundreds or thousands of years.

TEK and Indigenous land management contribute to healthy ecosystems as well as the prevention of climate catastrophes. But as long as threats to Indigenous rights and Indigenous sovereignty—which are tied to Indigenous knowledge systems and practices—continue, Indigenous-led solutions to the climate crisis will be impeded. Removing barriers to Indigenous rights and sovereignty ensures that Indigenous communities can implement effective solutions to the climate crisis according to their traditional expertise and the needs of their communities.

And, learning about the ways in which many Indigenous communities have historically managed to simultaneously meet the needs of people while enhancing the local environment can help the rest of society reorient its relationship with nature.

Rights of Nature

The Rights of Nature are laws that recognize Earth and its ecosystems as living beings with the inalienable right to exist and flourish.

This paradigm shift is a significant departure from the dominant legal system’s treatment of nature as an inanimate object to be owned as property and consumed or sold as a commodity. The Rights of Nature instead reflect an Indigenous worldview, one in which nature is alive and humanity is a part of nature—and not separate or dominant over it.

The Rights of Nature also recognize the authority of people to enforce these rights, making the Rights of Nature both an issue of environmental protection and community rights.

Why are Rights of Nature necessary?

The Rights of Nature directly address the legal system of environmental protection, which not only fails to protect the environment but also permits its destruction.

Rights are the highest form of protection within the legal system in the U.S. and in many places around the world. However, because this legal system currently views nature as “property” and not as an entity with rights, anyone who owns land can use it as they see fit. This allows and encourages governments and corporations to pursue profitable projects even if they devastate the environment and local communities. Even when there are environmental protections already in place, they’re often limited to very specific cases or used reactively.

Most existing environmental protections are reactive and not preventative, intended to limit some of the more adverse effects of destructive projects without actually stopping them from happening.

This is largely because the regulated industries—not the environmental protection agencies—write the regulations. When the federal or state governments issue permits for destructive projects, the burden is on local communities or individuals to finance challenges to those permits. These efforts are often unsuccessful given the outsized economic power that corporations hold. And even when these efforts do succeed, corporations can wield their political influence to rewrite the regulations through the legislature. Corporations will also often use their political and economic influence to pass preemptive laws that prohibit citizens from passing legislation that protects the environment.

Granting rights to nature has the potential to bring the decision-making process down to the those directly impacted by corporate and governmental activities that are toxic to the health of the environment and communities.

Through Rights of Nature, nature is afforded the highest level of legal protection within the current legal system and is able to be defended in a court of law whenever it’s harmed. This means that when environmental degradation occurs, individuals or communities can legally represent nature in court and invoke its rights in order to avoid or rectify the damage. Without rights, nature will continue to be conceived of as “property” subject to the economic interests of governments, corporations, and other powerful entities.

If nature has rights, everyday citizens have a powerful avenue for not only stopping the destruction of the environment, but also for prohibiting the destruction from happening in the first place.

Rights of Nature in practice

Efforts to grant legal rights to nature have become a global movement, one largely led by Indigenous peoples but pursued by non-Indigenous communities alike.

Ecuador became the first nation to incorporate the Rights of Nature into its constitution in 2008, including four Rights of Nature principles:

- Nature has the right to exist

- Nature has the right to regenerate

- Nature has the right to maintain its natural cycles, functions, and processes

- Nature has the right to restoration.

Similar efforts to grant rights to nature are growing in the U.S., largely in local communities who are taking environmental protection into their own hands. In 2005, the Navajo Nation banned uranium mining by invoking its traditional laws. In 2006, Tamaqua Borough banned the dumping of toxic sludge, becoming the first community in the world to codify the Rights of Nature into law. Since then, dozens of other communities throughout the U.S. have pursued Rights of Nature initiatives.

Strengthen Democracy

One of the biggest barriers to effectively addressing the climate crisis is the lack of a strong democracy that responds to the will of the people and to the needs of the environment.

In the U.S., the political system tends to protect corporate interests at the expense of the environment and local communities.

Unless we have a political system that responds to the will of ordinary citizens and to the needs of nature, progressive action on the climate crisis and the interrelated social injustices will be stalled.

What is the state of democracy now?

In many ways, corporate power has subverted democracy.

Because of U.S. Supreme Court rulings such as in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which lifted restrictions on political campaign financing for corporations and other groups, the political system in the U.S. is heavily influenced by corporate interests.

Often, large corporations—such as those in the extractive industries—use their massive amounts of wealth to heavily sway which politicians are elected as well as which laws are passed. Because these corporations prioritize protecting and growing their assets, they tend to favor politicians and laws that allow them to exploit people and the environment for profit. Given that just 100 corporations are responsible for 71% of all industrial emissions, we can’t ignore the immense impact that corporations have on the environment.

Not to mention, when ordinary citizens push for meaningful climate action—like shifting away from a fossil fuel economy—corporations whose profits depend on continuing business as usual often obstruct these efforts through the legislature or legal system.

This is particularly dangerous when corporations attempt to evade responsibility for their human rights violations and catastrophic ecological damage. ExxonMobil’s efforts to limit climate change policies and Chevron’s attempts to use the U.S. court system to avoid accountability for its toxic waste in the Amazon are clear examples of how corporations often use their disproportionate political power to resist and impede meaningful action to address the climate crisis.

Strengthening democratic rights

According to the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights, expanding civil and political rights paves the way for ordinary citizens to prohibit activities that harm the environment as well as people’s health and livelihoods.

These rights include the right to

- Clean water

- Sustainable agriculture

- Be free from chemical trespass

- A livable climate

- Sustainable waste management

- Sustainable energy

- Local control over large-scale development

- Constitutional protections in the workplace

- Be free from pollution

Because of the obstacles that corporate power poses for addressing the climate crisis, it’s critical to strengthen democratic rights so that people—not those with disproportionate political power—have ownership of the decision-making processes that shape the health of the environment and the health of their communities.

Regenerative Economy

Currently, the dominant economic system around the world is based on the extraction and exploitation of both people and the planet.

This extractive industrial system, which treats nature as a commodity and certain communities as disposable, is severely limiting the planet’s ability to sustain life. As the world’s economies strive for unlimited growth, humanity’s demand for and consumption of energy and resources continues to grow as well. Humanity’s annual consumption of Earth’s resources far exceeds what the Earth can regenerate in a year, and until we reorient the world’s economies to be in balance with nature, we risk catastrophic ecological damage.

A transition from the extractive industrial economic system to a regenerative economy would not only strengthen Earth’s ability to support life, but would also ensure that the benefits of economic growth are distributed fairly and equitably.

What is a regenerative economy?

According to Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, a regenerative economy is an economic system that produces, consumes, and distributes resources in balance with nature while ensuring equity and justice.

Unlike an extractive economy, a regenerative economy prioritizes a healthy environment and healthy communities over profits. It ensures access to healthy foods, renewable energy, clean water and air, and living-wage jobs that respect the rights of all workers. A regenerative economy is structured around community governance as well as community ownership of work and resources. This includes the democratization of how we produce and consume goods, as well as the re-localization of the global economy.

Re-localization includes

- Producing food and goods to be used locally, rather than to ship overseas

- Reducing the amount of energy needed for packaging and transporting goods

- Localizing food production, which saves energy otherwise needed for long distance transport and supports local producers

- Reducing waste, especially from disposables and excess packaging

- Building resilience within local regions in the case of economic collapse or climate disaster

Degrowth

Re-localization is a key aspect of degrowth, a process that counteracts the current economic system’s orientation towards infinite growth.

Degrowth is the equitable contraction of the wealthiest nations’ economies so that they operate within the biophysical limits of Earth’s living systems. Less than 20% of the global population consumes 80% of the world’s resources, and just 10% produce nearly half of global consumption-based emissions. This makes it clear that the climate crisis is at its core as much about the imbalance between humanity and nature as it is about the imbalance within humanity.

Equity is a critical consideration for climate change solutions because the extractive economy not only extracts from nature, but it also extracts from marginalized communities. At the same time, this economic system excludes these communities from the benefits of economic growth while disproportionately burdening them with the impacts of climate change.

The extractive economy encloses wealth and power, while undermining democracy by creating the conditions for those with disproportionate wealth or corporate power to override the needs of nature and ordinary citizens—particularly those who are already disadvantaged. Often, these injustices are justified by the pursuit of economic growth and “progress.”

However, striving for economic growth without regard for the biophysical limits of earth’s living systems and without regard for the impacts on marginalized communities is a distorted view of progress, one that ignores the realities of the climate crisis.

Shift Worldview and Culture

The climate crisis and its interrelated social, economic, and political crises are all the unintended result of a dominant worldview that has become destructive for all life on Earth.

This worldview encompasses a multitude of beliefs or assumptions that underpin our behaviors as a species. Though much of humanity thinks it’s behaving rationally by pursuing “progress” and economic growth, many of our behaviors are depleting the Earth’s ability to sustain life—jeopardizing ourselves, other species, and future generations.

The cultural myths of our destructive worldview

Below are four cultural myths that are part of the dominant worldview driving the climate crisis.

Myth #1: The Illusion of Separation

The core of the destructive worldview driving the climate crisis is the illusion of separation.

The illusion of separation promotes the idea that humans are separate from each other and separate from Earth. This false sense of separation has resulted in humanity operating along a hierarchy in which humans have supremacy over nature and other species, while some humans have supremacy over others. This hierarchy reinforces the illusion of separation while justifying the exploitation of people and the planet.

However, all of humanity is deeply interdependent and interconnected with each other and with Earth. Humanity’s survival is inextricably tied to the health of the planet and the wellbeing of others. We’re not individuals who can succeed by ourselves if only we focus on our own success and outcompete everyone else. And we aren’t somehow outside of nature, with a right to do with it as we see fit. Rather, humanity is a part of nature and comes from the same source of life that connects us to all other life forms. This interconnectedness means our actions have consequences for all—including ourselves; what we do to others has ramifications for our own lives, and what we do to Earth we do to ourselves.

The antidote: Recognizing and embracing our interconnectedness with each other, with other species, and with the natural world that we are all a part of.

Myth #2: The Mechanistic View of Nature

In addition to viewing nature as separate from humans, most of society also has a mechanistic view of nature in which people relate to nature as a non-living object. Through this perspective, nature is treated as a machine made up of separate parts that humans can control, use, and dispose of as we see fit. It also means that humanity relates to nature as solely existing for and only having value if it can be commodified for our short-term gain. This makes it easier to justify degrading nature and can make us blind to the impact we have on Earth’s living systems, other species, and future generations.

The antidote: Relating to nature as a living being with an inalienable right to exist and thrive.

Myth #3: Infinite growth

The industrial extractive economy is oriented towards infinite growth, which is the idea that limitless economic growth is achievable.

The false promise of infinite growth is destructive because it disregards the ecological and social limits of expanding the economy. This paradigm promotes limitless extraction and consumption of energy and resources, which is depleting the earth’s resources faster than it can regenerate them. It also justifies the concentration of wealth and power as well as ecological destruction—all for the sake of “progress.” Not to mention, the notion of infinite growth encourages us to tie material consumption and accumulation to self worth. This in turn promotes a mass consumerist culture, one that alienates humans from ourselves, from each other, and from Earth.

The antidote: Living in balance with nature and finding contentment in having enough.

Myth #4: Throwaway Resources, Species, and People

The climate crisis has revealed that in many ways, humanity believes that there are throwaway resources, species, and people.

In other words, much of society has come to accept that some resources, other species, and certain groups of people will necessarily have to be sacrificed in order for “progress” or “growth” to occur. Society has come to accept that the extent to which people can use something or someone is a measure of value, which encourages people to dispose of anything or anyone that no longer serves their interests.

The antidote: To relate to Earth as sacred, and to ensure a thriving world for all people and all species.

Climate Justice

The climate crisis is not simply an environmental issue.

Rather, the climate crisis is inherently a social justice issue just as much as it is an ecological one. What humanity does to Earth inevitably impacts our communities. And unless we embrace and center climate justice in how we address the climate crisis, destruction of the earth will continue and those who are most vulnerable to climate change will have to pay a disproportionate price.

The link between climate change and justice

Although climate change impacts all life on Earth, how those impacts are experienced aren’t the same for everyone.

Because our current political and economic systems disadvantage certain communities, the resulting social inequalities are compounded and exacerbated by disruptions in the environment such as drought, natural disasters, or ecosystem collapse.

In particular, marginalized communities are more vulnerable to climate change impacts because they often lack access to resources to offset those impacts as well as access to spaces where decisions that impact their communities are shaped.

These frontline communities, which tend to be predominantly poor and/or BIPOC communities, are at higher risk of living and working near hazardous sites, are more exposed to toxins and pollution, and are often excluded from adequate natural disaster relief.

Climate justice is where justice for the planet and justice for people intersect.

Often, environmental issues are addressed separately from social justice issues. However, at the heart of the climate crisis are relationships of domination and exploitation of both people and planet. These relationships emanate from a false sense of separation—separation between ourselves and others as well as separation between humans and nature. This sense of separation makes it easier for us to “other” nature and certain peoples, and this othering justifies and reinforces their exploitation.

Climate justice provides a powerful pathway to striking the root cause of the climate crisis, while ensuring that nobody is left behind in the process or the outcomes of creating a better future.

Climate justice includes

- An intersectional approach to understanding and addressing the climate crisis

- Intergenerational collaboration and youth leadership

- Ecofeminism

- Decolonization, including the recognition and strengthening of Indigenous rights

- Addressing environmental racism and centering BIPOC leadership in the climate justice movement

- Economic justice and a Just Transition to a regenerative economy

- Food justice, food sovereignty, and the re-localization of food systems

- Centering the voices, perspectives, and solutions of frontline communities

- Grassroots community-based action and decision-making

By ensuring solutions to the climate crisis address both the environmental and social justice implications of climate change, we’re able to address the climate crisis as the political and ethical issue that it truly is while striking at the root causes of the destruction to our planet and to our communities.